09.11.2022: Update with reaction to the announcement from the High Level Expert Group (HLEG)

The UN High-Level Expert Group on Net-Zero Emissions Commitments of Non-State Entities (HLEG) launched their eagerly anticipated findings with the headline “It’s Time to Draw a Red Line Around Greenwashing”. While we commend the leadership by the UN Secretary General Antóonio Guterres and the effort by the Expert Group, the final recommendations of the group will not be enough to achieve this headline because they do not close various loopholes that many non-state actors, in particular businesses, have exploited. Below we highlight key issues where further scrutiny by the community is needed.

The UN Secretary General António Guterres called for the HLEG to make recommendations to address the “deficit of credibility” of net zero targets, to “develop stronger and clearer standards for net-zero emissions pledges”. That deficit of credibility had arisen despite the many voluntary initiatives that have proposed their own standards for net zero targets or elements of it. But the group’s recommendations largely repeat the existing guidelines of these voluntary initiatives and add very little in terms of new requirements. The HLEG report even endorses the voluntary initiatives by name, indicating explicitly that companies should be simply recognised as net zero aligned if they are following the (in some cases draft) guidelines of initiatives like SBTi, PCAF, PACTA, TPI, ISO, IC-VCM and VCMI. This misses to point out the urgent need for improvement of existing methods and approaches, as highlighted for example in a recent open letter on science community concerns. It is essential that the standards and criteria of these initiatives will continue to be held accountable for their integrity with science.

The recommendations represent a high-level declaration of minimum criteria for integrity, which might address some of the most basic forms of greenwashing. It is a positive development to have a high-level signal that net zero targets must cover entire business entities and all of their emission sources, and that companies with net zero targets should cease further exploration and exploitation of fossil fuels. These statements entail profound consequences for fossil fuel supply industries that have not been well covered by existing voluntary initiatives.

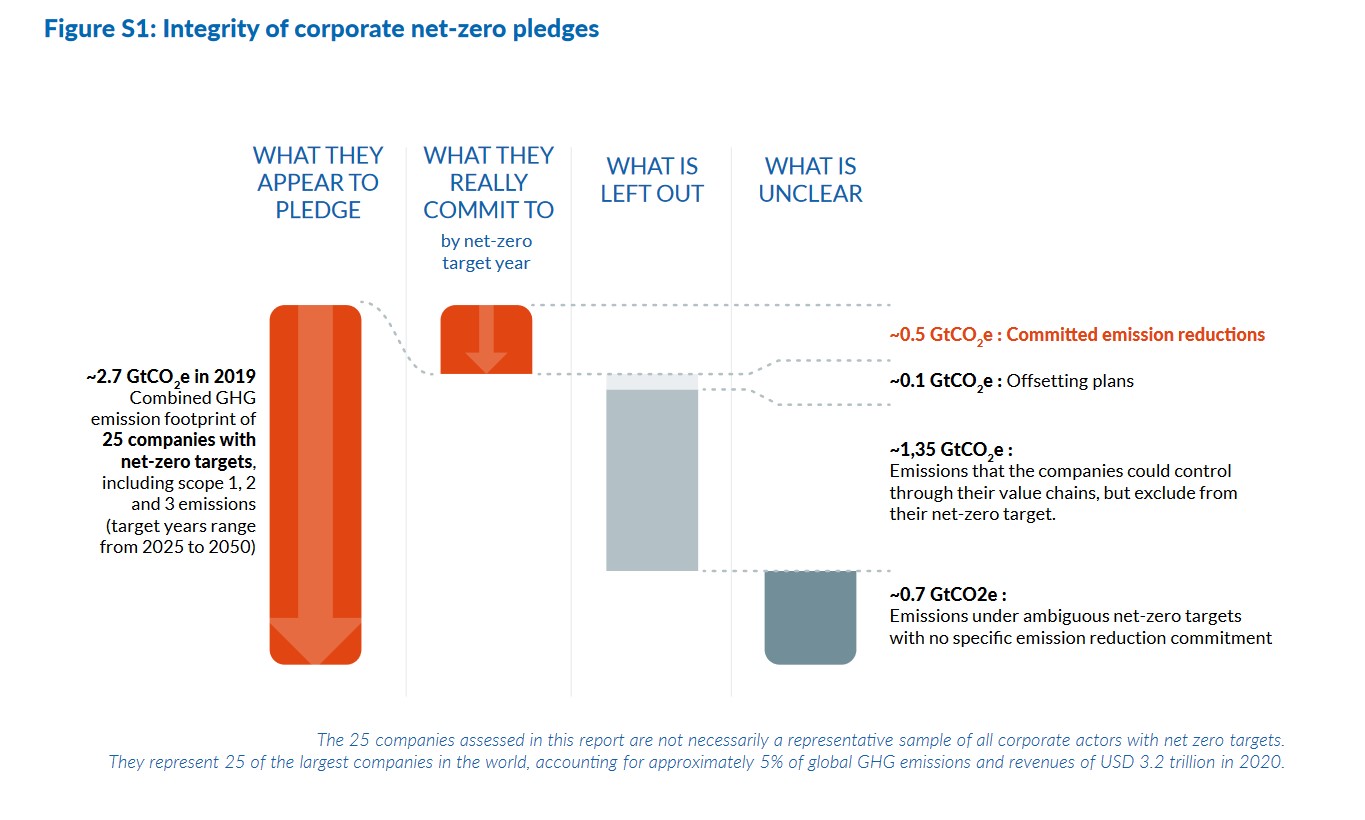

But the recommendations do not include the seemingly obvious requirement that net zero pledges must actually entail a commitment to deep decarbonisation. Although this might seem evident, it is alarmingly far from reality: our analysis of 25 major global companies showed that half of these companies do not make concrete commitments to any emission reductions at all, while those who do commit on average to only 40% emission reductions in their “net zero” target years (see Figure S1).

The HLEG’s recommendation on “Using Voluntary Credits” is also wholly insufficient. This recommendation lacks a clear limit of the maximum role for offsetting and offers ambiguous and contradictory criteria: high-quality carbon credits with additionality and permanence are recommended, but specific initiatives that do not deliver on these basic criteria are explicitly endorsed.

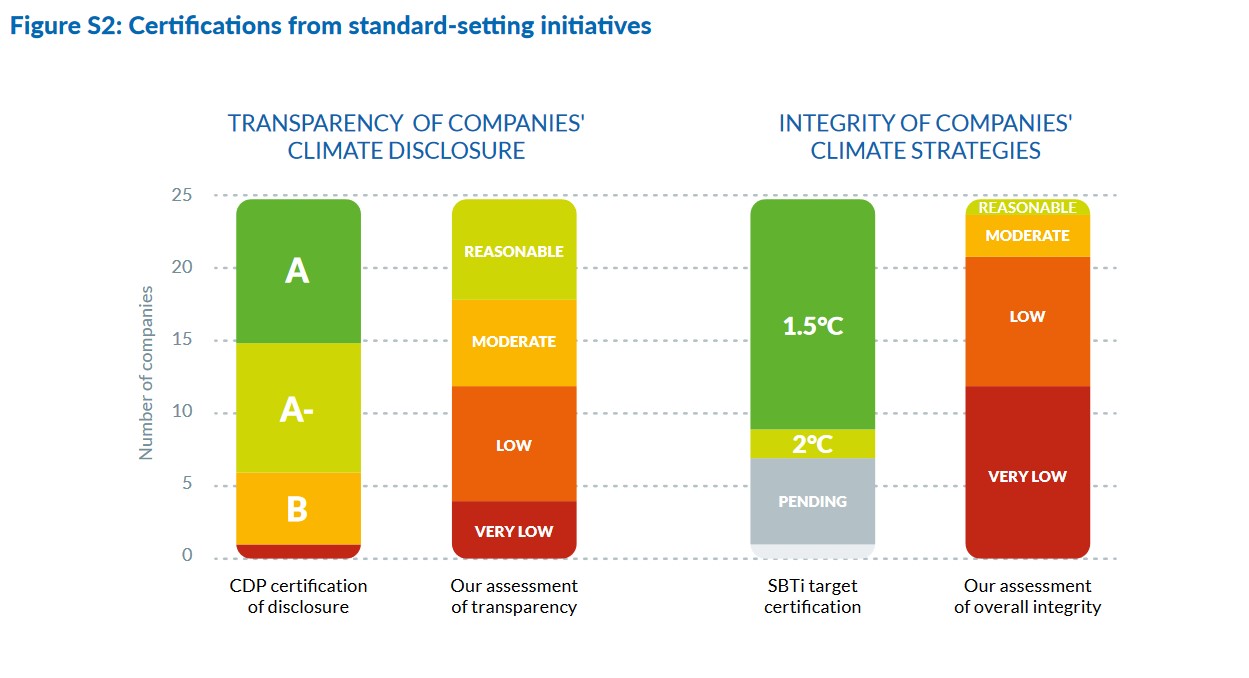

Many of the recommendations send a sensible high-level signal. However, for the most part, these rules already existed and formed the basis of the framework upon with companies have already been making contentious claims. Aside from methodological blind spots, a key issue is that existing voluntary initiatives were not able to ensure that the recommendations are really applied. Our extensive inspection of companies’ targets often reveals specific details or loopholes that significantly undermine or diminish companies’ apparent ambition, even if they appear at a glance to be meeting such high-level recommendations. For the majority of the 18 companies assessed in the 2022 CCRM report with an SBTi approved 1.5°C- or 2°C-compatible target, we would consider that rating either contentious or inaccurate, due to various subtle details and loopholes that significantly undermine the companies' plans (see Figure S2). Unlike with well-designed regulation, there appears to be no significant accountability or consequences for using creative accounting tricks to violate the guidelines of voluntary initiatives. Although the HLEG was right to highlight an important role for these initiatives in convening actors, the Group should – based on the ample available evidence – have concluded that it has proven ineffective for those same actors to also play the role of assessing and validating companies’ pledges.

Accordingly, the HLEG’s 10th recommendation – that the recommendations are picked up by regulators and not left to voluntary initiatives alone – is its most important. We need to recognise that these voluntary initiatives are not an equivalent alternative to regulation and the independent judiciary that comes with it.

Original blog content from 03.11.2022

At COP26 in Glasgow, UN Secretary General António Guterres set out a clear call to action for raising the credibility of corporate climate action and increasing scrutiny. One year on, ‘voluntary’ corporate climate action remains mired in ambiguity and misleading claims. At COP27, a number of initiatives plan to launch new guidelines with recommendations to help companies, investors, consumers and regulators differentiate real climate leadership from greenwashing. This body of guidance must require companies making bold climate pledges to actually commit to urgent deep decarbonisation of their value chains this decade. As things stand it looks like an inconsistent patchwork of recommendations may emerge, with ambitious pillars for climate action diluted in the name of compromise.

The overwhelming majority of corporate net-zero pledges are not underpinned by plans to rapidly and significantly reduce emissions.

Corporate net-zero targets and claims are far less ambitious than they seem at first sight and distract from critical short-term action. Analysis we published earlier this year found that the net-zero pledges of 25 of the world’s largest companies amounted to a commitment to reduce emissions across the value chain by just 40%. Only 3 of those companies committed to reduce emissions across their value chain by at least 90%; many others excluded scope 3 emissions or used creative accounting tricks, including offsetting, to achieve ‘net-zero’ emissions.

The high number of false net-zero pledges makes it harder for truly ambitious companies to stand out from the crowd. A minority of companies commit to deep emission reductions across their entire value chain, invest in innovative technologies with the potential to drive transformational change, and support suppliers in decreasing their emissions. It is currently an insurmountable task for consumers, investors or regulators to distinguish between greenwashing and real corporate climate leaders.

Unsubstantiated net-zero pledges also divert attention away from the need for short-term action. Global emissions must be halved between 2019 and 2030, yet the 25 multinationals mentioned above committed to reductions of only 23% in that period. For context, if all companies worldwide were to follow the example of these global corporates touting their ‘climate leadership’ in charting a trajectory for only a marginal reduction of emissions between 2019 and 2030, that would put us on a path for warming of well above 2°C. Time to wake up.

Net-zero pledges are not the gold standard if they greenwash carbon-intensive industries and distract from the fact that there are no realistic prospects for deep decarbonisation of certain business models. Companies active in sectors such as oil and fossil gas extraction, artificial fertiliser or meat and dairy sectors increasingly set net-zero targets, but often these represent merely a commitment to decarbonise a discrete aspect of their carbon-intensive production process. Installing solar panels on the roofs of meat packaging facilities, or firing oil refineries with biomass, will not have any meaningful impact to decarbonise sectors whose continuing levels of activity are simply incompatible with decarbonisation trajectories. Such net-zero pledges are likely to mislead consumers, investors and regulators and distract from the much-needed transition to decarbonised business models. We need to request transparency on the decarbonisation prospects of these industries, rather than sending a blanket request for net-zero promises from all that simply encourages creative accounting and misunderstandings.

Companies increasingly exploit the wild west of unregulated offsetting claims. There is a lack of regulation on net-zero and offsetting claims, allowing companies to falsely advertise ‘climate neutral’ products and services. Major companies with net-zero commitments plan to use non-permanent removals from forest-related projects to offset their emissions, although the temporary nature of these carbon removals makes them unsuitable for claiming to neutralise emissions that can stay in the atmosphere for centuries to millennia. Claims around net-zero and offsetting are increasingly becoming a liability for companies, with legal cases brought against Arla in Sweden, KLM in the Netherlands and SK Lubricants in South Korea for instance.

Science instead of compromises should underpin guidelines for corporate target setting

In the absence of regulatory efforts, existing guidelines and initiatives are lending credibility to unsubstantiated net-zero pledges. All 25 companies included in the Corporate Climate Responsibility Monitor are members of initiatives that are vetted partners of the Race to Zero campaign; most of them have SBTi-verified 2030 targets and CDP A-ratings. Companies use these memberships and certifications to advertise their net-zero pledges, misleading consumers, investors, and regulators about their real climate ambition. Eighteen companies in the Corporate Climate Responsibility Monitor have an SBTi approved 1.5°C (or 2°C) compatible target. However, for the majority of these 18 companies, we consider that rating either contentious or inaccurate, due to various subtle (but important) details and loopholes that significantly undermine the companies' plans.

Guidelines and standards from voluntary initiatives can only positively influence the ambition level of corporate targets if they are underpinned by science, rather than compromise. Many of the weaknesses and loopholes in company net-zero targets arise from the fact that profit-driven businesses play an instrumental role in setting the rules. The climate crisis is an issue of physical sciences, where the outcomes do not care for compromises of convenience. If guidelines and rules from voluntary initiatives entail compromises that lead to deviating from science-aligned pathways for 1.5°C, then by definition following their recommendations will not be enough. That should be evident, yet it does not underpin the process for determining the rules that existing voluntary initiatives have pursued to date.

Guidelines by the International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO) could facilitate more robust and ambitious corporate targets. ISO is expected to present guidelines for corporate net-zero targets at COP 27 in Sharm al-Sheikh. The process of drafting these guidelines has oscillated between text that could sufficiently safeguard ambition, and text that could facilitate greenwashing, as the scientific and business communities took turns to have their say. The latest draft contained a contradictory combination of both elements, but there were very encouraging signs which we will be looking out for in the new guidelines. Most importantly, the latest draft of the guidelines required companies with net-zero targets to actually make commitments to the deep reduction of their GHG emission footprints. Companies in sectors where there are no clear prospects for decarbonisation, and companies that are simply unwilling to embark on decarbonisation trajectories, should not claim to be on a net-zero emission pathway. That might sound obvious, but it remains a long way from the current ambiguous reality. Emission reduction commitments must cover companies’ full value chains and they must be in line – in the short- and long-term – with 1.5 °C-aligned benchmarks from the scientific literature. Any use of contentious offsetting practices must be completely independent of these clear principles for emission reduction targets.

The UN High-Level Expert Group’s recommendations for corporate net-zero targets may also contribute to improved quality of voluntary standards and regulatory efforts, but the devil of corporate net-zero targets likely remains in the details. After UN Secretary General António Guterres called for more scrutiny and credibility in corporate climate action at COP26, he appointed the UN High-Level Expert Group on Net-Zero Emissions Commitments of Non-State Entities (HLEG) in March this year. The HLEG will release its recommendations at COP27 on current standards and initiatives for setting net-zero targets, as well as on how to translate existing standards and criteria into national regulation. Here too, we will be looking for science-aligned recommendations that challenge businesses and existing voluntary initiatives to move towards more credible plans, rather than another compromise seeking exercise.

The Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity initiative (VCMI) risks legitimising insufficiently ambitious approaches that are potentially misleading and detrimental to global climate action. In June 2022, the VCMI presented its ‘Provisional Claims Code of Practice’, with the aim of providing companies with guidelines for credible claims related to the use of carbon credits. However, the provisional ‘Claims Code’ fails to provide definitive guidance on the most relevant issues, including points as fundamental as whether carbon credits can be used to make offsetting, or ‘neutralisation’ claims (the text says opposing things in different places), as well as critical aspects such as credit quality and corresponding adjustments. Further, by proposing three labels (‘VCMI Gold: Net Zero’, ‘VCMI Silver’ and ‘VCMI Bronze’), the guidance seems to prioritise mass participation rather than setting a benchmark for high integrity. What is the scientific basis of awarding silver or bronze medals to approaches that fall short of full environmental integrity? Another issue is the undefined ‘carbon neutral’ label for claims on products, services and brands; in its current form VCMI recommendations allow product, service or brand specific net-zero claims without requiring that the companies they belong to demonstrate they are on track to meet their science-aligned targets.

Governments need to urgently ramp up regulation to address the policy gaps left by these voluntary initiatives and guidelines around corporate climate claims and reporting. The current situation demonstrates that regulators must not rely on voluntary initiatives or on consumer and shareholder pressure to drive truly ambitious corporate action. Company pledges should not be viewed leniently as merely voluntary philanthropic efforts, but rather recognised and scrutinised as a calculated response to win over consumers and investors who are already doing their part to apply pressure for climate action. Pledges must be credible and companies should be held accountable if they are misleading their consumers and shareholders, and placating this potential ambition raising driver.

Some governments are starting to recognise the dangers of unregulated climate claims and are developing measures to tackle them. For instance, the French government adopted a law prohibiting companies to make carbon neutrality claims unless they disclose their GHG footprint and emission reduction strategies. The European Union is working to develop a corporate sustainability reporting directive (CSRD). A draft of the regulation prohibits companies from offsetting their GHG emissions with carbon credits, and requires them to present plans to ensure their business model and strategy are in line with limiting global warming to 1.5°C.

In addition, governments must recognise – however reluctantly – that the current patchwork of voluntary guidance is unlikely to facilitate a race to the top for sufficient climate ambition without the need for policy intervention. In addition to these voluntary drivers and market forces, governments need to implement more comprehensive regulation to stimulate deep emission reductions across all economic sectors. Although such regulation might face resistance from laggards and cost political capital in some quarters, it is necessary to support truly ambitious corporates and avoid disadvantaging early movers. Companies need a clear signal that they will thrive by urgently and extensively cutting emissions throughout their value chain.

The Corporate Climate Responsibility Monitor aims to develop insights on the credibility of corporate climate target pledging, and the guidelines that underpin them, through analysing the transparency and integrity of major global companies’ climate pledges. We will publish the 2023 Corporate Climate Responsibility Monitor in February next year, covering 24 of the worlds’ largest companies. We will also shortly publish further practical guidance on ‘climate contributions’, offering recommendations on how companies can take greater responsibility for their emissions without offsetting.