Why the LNG export push by the US sets the world on fire

Almost five years ago, the International Energy Agency (IEA) warned that in a net-zero world there is no need for new fossil fuel supply. They repeated the message in 2023: no new long lead oil or gas projects fit in a Paris-compatible pathway.

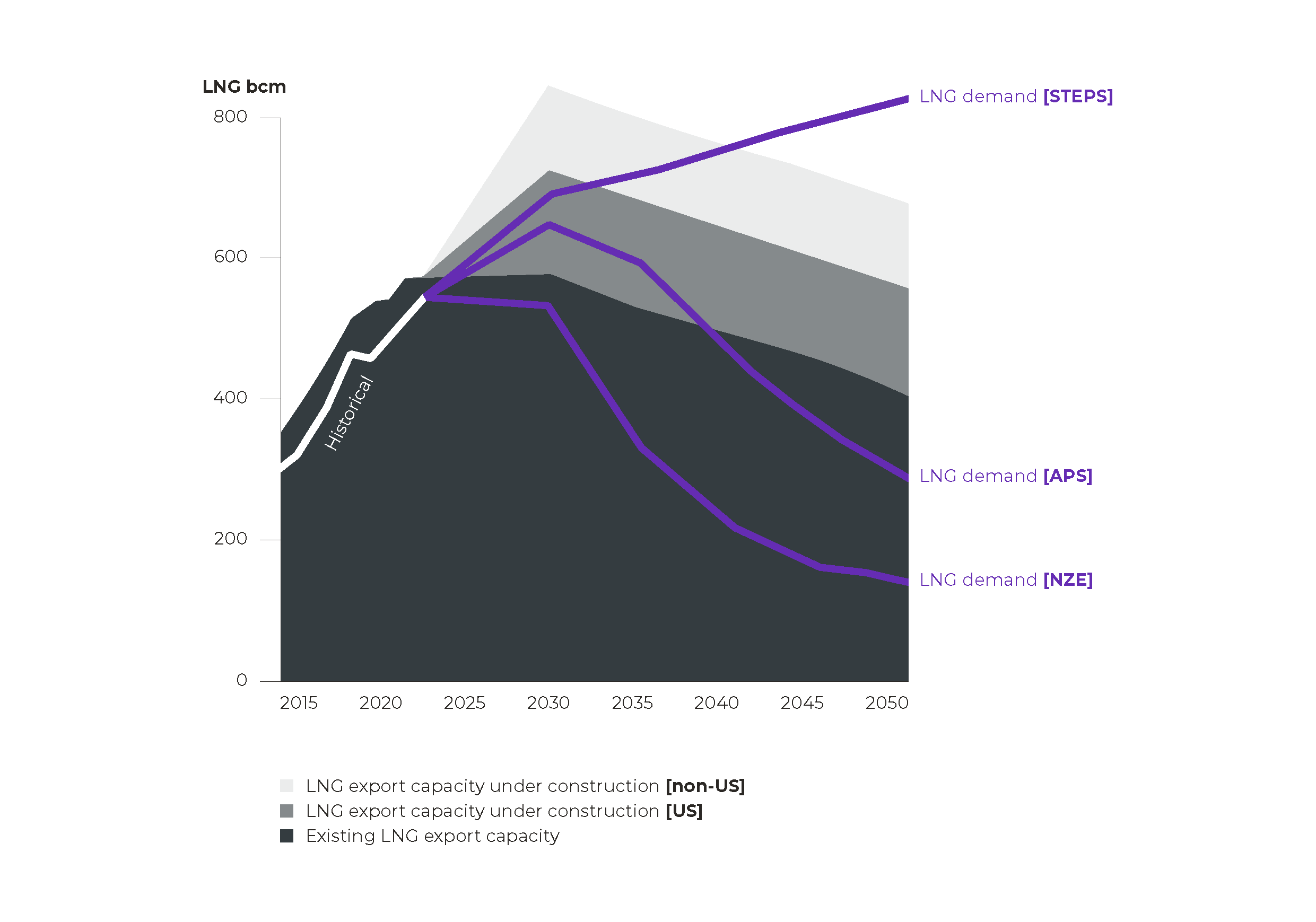

And yet the world is sprinting in the opposite direction. Global gas production rose to a new high in 2024, increasing by 2% compared with 2023. The United States, already the world’s largest gas producer, broke new production records in 2024, both driving and benefiting from the rapid expansion of global liquefied natural gas (LNG) trade. Globally, liquefaction capacity, which is key to bring the gas onto the global market, has swelled beyond 680 billion cubic metres per year – and developers are lining up an additional 1,544bcm, more than tripling the capacity existing today.

What happened, who is responsible, and how do we stop a gas boom that nobody ordered?

Energy security panic and industry spin

Covid recovery, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and a string of geopolitical crises have pushed energy security to the top of the global agenda. Gas, and particularly the supposed flexibility of LNG, has been sold by the industry as the cure-all for energy shocks and the cornerstone of energy security. The result have been rushed and costly decisions to build out import capacities, many of them vastly oversized, as we have for example shown for Germany. Far from providing stability, these investments lock in new dependencies that can be weaponised. This danger specifically looms over Southeast Asia, which is on track to account for 25% of global energy demand growth between now and 2035, and which is still struggling to redefine energy security in a way that breaks free from gas.

What helps the industry create demand for gas is the fossil lobby doubling down on its favourite myth: that LNG is a ‘bridge fuel’ which will cut emissions by replacing coal and helping transition to a decarbonised energy system, specifically in Southeast Asia. First of all, the claim ignores economic reality. As we increasingly see in major coal producers such as China and India, imported LNG cannot compete with cheaper alternatives like the rapidly expanding share of renewables, and is therefore ‘a bridge to nowhere’. Second, the environmental argument collapses as soon as you look closely at, for example, the lifecycle emissions of US shale gas-turned LNG shipped around the world, as well as the lock-in effects of LNG infrastructure development. The idea of LNG as a bridge in the energy transition is pure industry spin, with dangerous consequences for any country that buys into it.

A supply push the planet can’t carry

In less than a decade, the United States has vaulted to the top of the LNG export league. Along the Gulf of Mexico, export terminals are mushrooming to push the country’s vast shale gas reserves onto global markets. The ‘shale revolution’ left the US with more gas than it can consume at home, turning it into a net exporter. Every new terminal cements further drilling in existing shale fields and the expansion of new ones. US LNG exports are projected to climb by 10% each year until 2030 – and maybe beyond.

The US is not alone. Qatar is racing to expand its North Field project, aiming for an 85% increase in export capacity by 2030. Newly discovered reserves in countries such as Senegal and Mozambique are stoking hopes of joining the exporters’ club, often sold with promises of development rents that, as we have shown, are unlikely to materialise.

This supply wave is, obviously, wildly out of sync with climate goals. Even without the projects still on the drawing board, existing and under construction capacity already overshoots what is needed under any of the IEA’s LNG demand scenarios until 2040. The LNG capacity the US already has under construction would be enough to meet all projected demand growth under the IEA’s Announced Pledges Scenario (i.e. demand in line with policies that governments have pledged to date) and far exceed it after 2035. In a Paris-aligned pathway, the IEA’s Net Zero Emissions by 2050 Scenario, the picture is even starker: no new export infrastructure is required. On the contrary, much of today’s fleet would need to be wound down very quickly.

Forced dependency

Oversupply will drive prices down in the medium- to long-term. For emerging economies with rapid energy demand growth, cheap gas can look irresistible, but it risks trapping them in fossil dependence just as renewables become cheaper and more reliable.

Exporters know this. That is why US developers are racing to tie (largely Asian) buyers into 20-plus-year contracts. Already this year, US exporters have locked in volumes of more than 22bcm per year over two decades (see Table 1). These new deals, which alone already account for more than 10% of the LNG the world could demand in 20 years from now under the IEA’s Net Zero pathway, are being piled onto an already swollen supply glut, and they are unlikely to be the last we see this year. These deals bind countries to fuel they may not need, with the Trump administration even threatening tariffs to push them through. The result is forced dependency dressed up as energy security. It is a form of energy imperialism, pressuring countries to retreat from their climate commitments.

|

Terminal |

Buyer |

Volume bcm per year |

Duration |

|

Sabine Pass/Corpus Christi |

Jera |

1 |

21 years |

|

Port Arthur Phase 2 |

Jera |

2 |

20 years |

|

CP2 |

Eni |

3 |

20 years |

|

CP2 |

Sefe |

1 |

20 years |

|

CP2 |

Petronas |

1 |

20 years |

|

Lake Charles |

Chevron |

1 |

20 years |

|

Commonwealth |

Jera |

1 |

20 years |

|

Rio Grande |

Jera |

3 |

20 years |

|

Lake Charles |

Kyushu Electric |

1 |

20 years |

|

Commonwealth |

Petronas |

1 |

20 years |

|

Louisiana LNG |

Uniper |

1 |

13 years |

|

Rio Grande |

TotalEnergies |

2 |

20 years |

|

Rio Grande |

Aramco |

2 |

20 years |

|

Total: |

22 |

||

Who is to blame?

Those backing new LNG export infrastructure are enabling the production of more gas than the climate can bear. By lifting the export ban, and by signalling open disregard for the climate and the environment, the Trump administration played a decisive role in unleashing this supply-driven LNG boom. But the US is not the only one responsible:

- Importing countries’ governments are caving under pressure, agreeing to deals they neither need nor can realistically fulfil, as the recent US-EU energy trade deal illustrates, instead of standing firm and coordinating a pushback.

- Utilities are still signing long term off take contracts even though gas use must decline quickly to avoid the worst of the climate crisis. In Europe too, despite the bloc’s climate targets that require a rapid fall in fossil fuel consumption, companies like SEFE and Uniper have recently agreed to contracts lasting up to 20 years.

- Last but not least, the financial sector: Banks around the world have pumped more than USD 200 billion into LNG expansion since 2021. And insurers, including European firms that loudly warn about the climate crisis, are underwriting the very projects that fuel it.

The way out

The good news for the energy transition is that this bubble can still burst. The business case for LNG rests on manufactured demand and the illusion of never-ending fossil fuels rents. If governments refuse new fossil projects in mature markets, expose the ‘transition fuel’ lie in emerging ones, and coordinate on the energy transition, this business case would vanish. If utilities stopped undermining the transition by tying themselves to long term gas contracts, they could instead put their weight behind renewable expansion and grid modernisation. And if banks and insurers stop chasing short-term gains and finally close the loopholes in their exclusion policies, then finally also financing for fossil fuels will dry up.

The choice is clear. Keep feeding a gas boom no one ordered or call time on the fossil fuel industry’s last great bet and bring the world back on track for net zero.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of NewClimate Institute or the funder. The development of this article was funded through the IKEA Foundation.