Analysis by the Climate Action Tracker was published in Climate Policy, an international peer-reviewed journal, today. The paper identifies ten important, short-term sectoral benchmarks that key sectors need to take to help the world achieve the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C limit.

This new article addresses the questions to be discussed in the Paris Agreement’s 2018 Facilitative Dialogue, to be known as Talanoa Dialogue: “Where are we?”, “Where do we want to go?” and “How do we get there?” In particular for the last question, this paper adds actionable advice to policy makers.

All key sectors—energy generation, road transport, buildings, industry, forestry and land use, and commercial agriculture—have to begin major efforts to cut emissions by, latest, 2020. By 2025 they should have accelerated these efforts in order to reach globally aggregated zero carbon dioxide emissions by mid-century, and zero greenhouse gas emissions overall roughly in the 2060s.

The article, built on the Climate Action Tracker’s earlier report, warns that in today’s carbon-constrained world, if one sector were to do less, particularly the energy, industry and transport sectors, they would leave a high-emissions legacy for several decades. Lack of action could also result in a failure to set in motion the system changes needed to achieve the required long-term transformation.

The good news is that for most of the benchmarks the CAT analysis finds signs that a transition is already underway, though acceleration is required. Achieving these ten steps is possible and would put the world on a pathway to limit global temperature increase to 1.5°C.

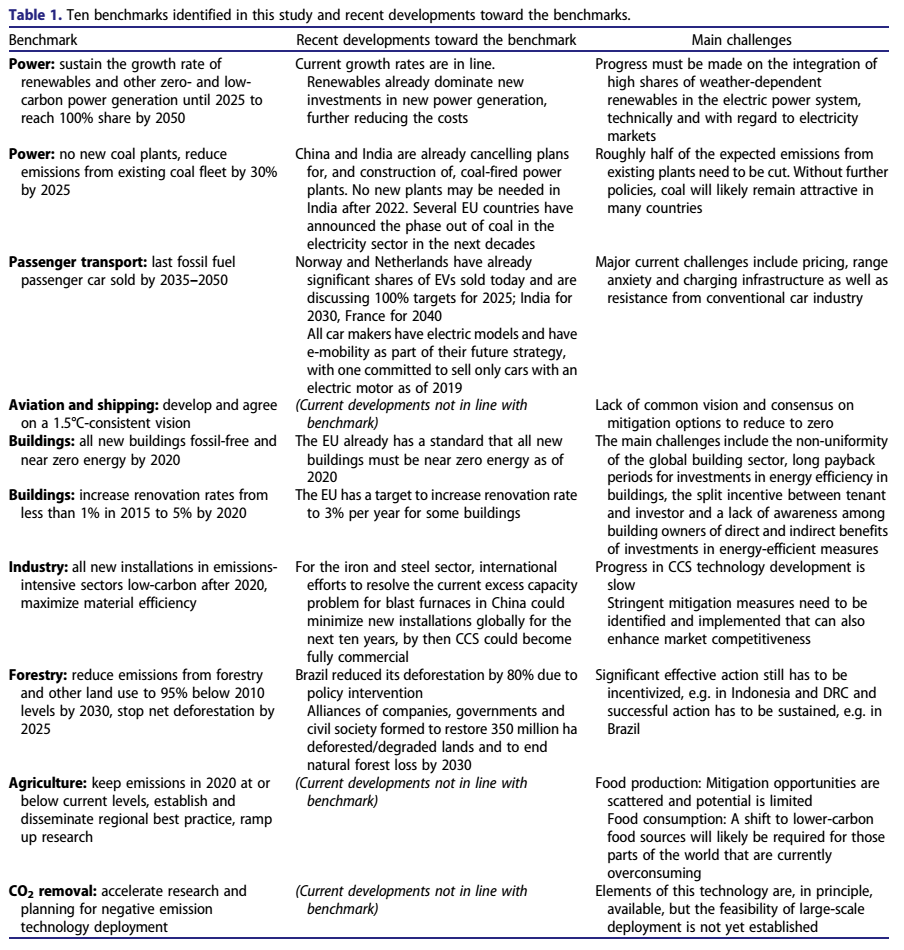

The full list of Climate Action Tracker’s ten short-term benchmarks:

The first and most important sector identified by the CAT is the electricity sector, which makes up one quarter of global emissions. It needs to undertake the fastest transformation, and must be fully decarbonised by 2050.

If renewables were to continue to grow at today’s rate through to 2025, it would set this sector on a path to full decarbonisation—and the power system and electricity markets need to prepare for this transformation.

The analysis separates out coal power into a separate step, concluding that no new coal-fired power plants can be built under a 1.5°C pathway, and that emissions from coal must come down by 30% by 2025—and 65% by 2030.

The other sector with much promise is the road transport sector, where the analysis finds that no fossil fuel-powered car can be sold after 2035–2050 in a 1.5°C scenario. There are early signs of this happening with the uptake of electric vehicles in several countries having skyrocketed in recent years. This is in stark contrast to the aviation and shipping sectors, where there is no overall global vision on how to achieve zero emissions.

Industrial production is expected to grow significantly through to 2050, but emissions need to be reduced by well over 50% by then. From 2020 onwards, all new installations need to be built according to the best available low carbon technology standard, which, for the steelmaking sector, for example, excludes building conventional blast furnaces. Large emission reduction potentials also exist in the building sector, where low-emissions solutions have been available for years, but adoption has been slow.

The last step in the CAT list focusses on negative emissions, where the scientists list a range of important steps that need to be taken in the next five to ten years to prepare for the sustainable and safe deployment of these technologies by mid-century.