As the Government of Indonesia prepares to publicly launch its first iteration of plans to deliver on the goals of the Just Energy Transition Partnership it announced one year ago, we take a look at implications for the workers and communities that currently depend on its large and growing coal sector. The ‘Comprehensive Investment and Policy Plan’, or CIPP, will set out a transition pathway towards a cleaner power sector to drive Indonesia’s economic development in the coming decades. It needs to offer both concrete policies as well as financial support packages to ensure that justice – particularly for those employed in the coal sector and their dependents – sits at the heart of the transition.

An energy transition with bold aims needs public investment today in reshaping coal communities

Today, the Indonesian economy is powered by a large and growing fleet of relatively young coal plants. With coal generation capacity set to almost double nationally this decade, the domestic coal value chain maintains hundreds of thousands of jobs, concentrated in a few regions of the vast archipelagic nation. At the same time, the Government of Indonesia has committed to a shift away from reliance on domestic coal, towards clean technologies and infrastructure, with the support of public and private finance commitments set out in Indonesia’s Just Energy Transition Partnership, or ‘JETP’. This partnership aims to set out a pathway to first limit, and then cut, emissions from Indonesia’s electricity sector and help drive its economic growth through rapid scaling-up of renewable energy, firmly grounded in a vision to become a developed country by the time it marks 100 years of independence in 2045.

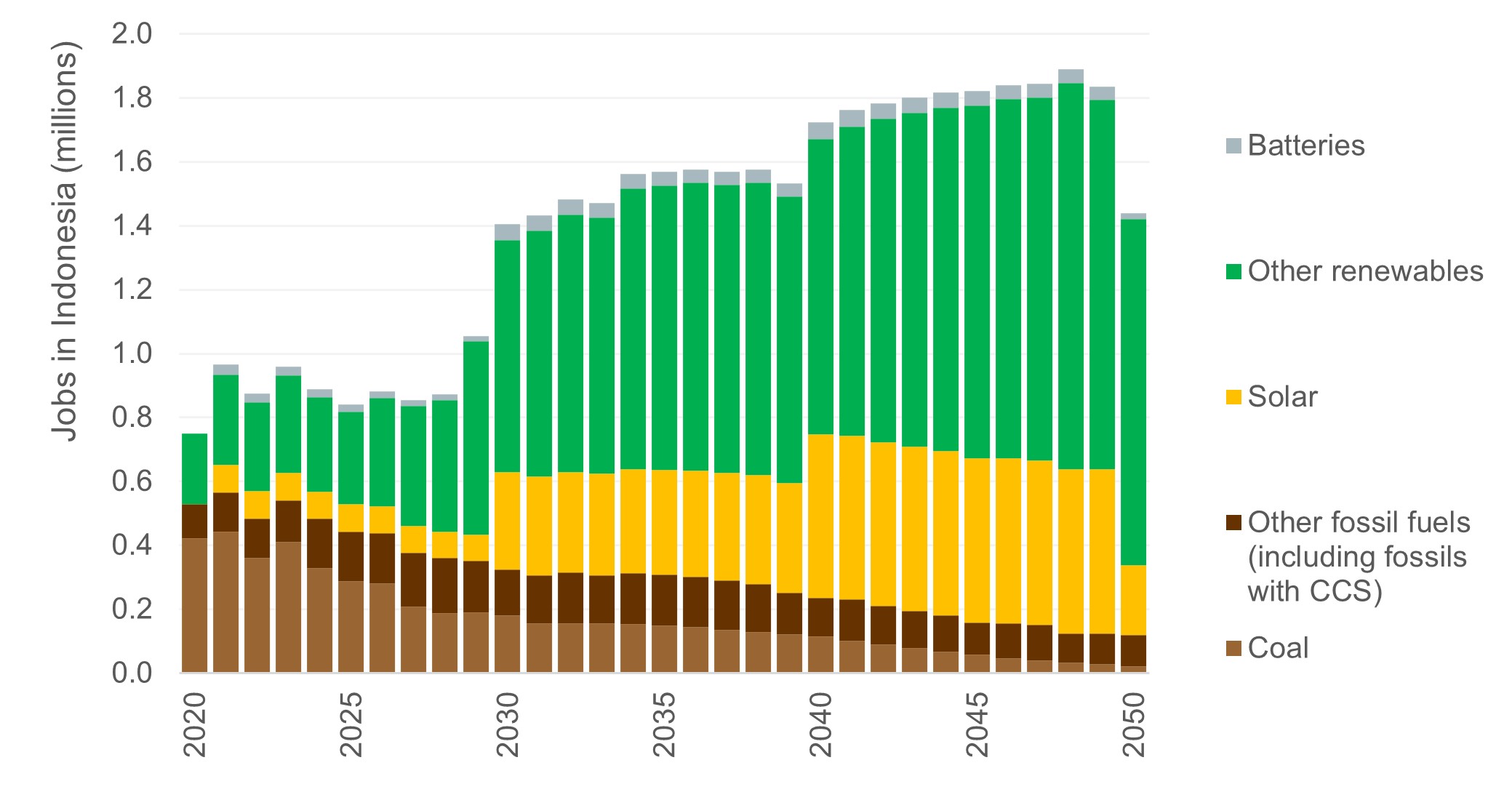

In a recent economic analysis by NewClimate Institute and the Institute for Essential Services Reform (IESR), we find that achieving the targets set out in Indonesia’s JETP Joint Statement could support one million domestic jobs in the renewable electricity sector by 2030. In parallel, coal sector jobs tied to the power sector are set to fall from their current peak of around 400,000 to less than half by the turn of the decade, as the ongoing boom in new coal plant capacity additions dries up. However, the JETP process has, up to now, drawn little attention to the barriers these coal workers and their communities may face in finding alternative employment.

Empowering workers dependent on coal-value chains to take advantage of the new job opportunities created by the transition requires early planning and mobilising financial and institutional capacities today. Coal workers risk being left behind in Indonesia’s energy transition without targeted investments in the expansion of re-training opportunities, measures to facilitate their re-location, as well as provisions for temporary income support.

Our initial findings indicate a need for at least USD 1-2 billion (IDR 16 trillion) in investments this decade to enable a smooth transition for coal workers, focused on those currently employed in planning and constructing coal plants. In the following two decades, financial support will then need to shift more towards facilitating an exit for those operating and maintaining coal plants, and those working in the mining sector.

The vast build-up of solar and other renewables could in theory provide new job opportunities for former coal workers

The JETP sets more ambitious energy targets for Indonesia, including a peak in power sector emissions by 2030, net-zero power sector emissions by 2050 and 34% renewable power generation by 2030. Given the country’s strong reliance on coal-fired electricity, the Joint Statement by Indonesia and the International Partners Group made a year ago also emphasises the importance of delivering a just transition for coal and coal-dependent communities, with the aim to create new opportunities for low-carbon employment and economic development.

Using NewClimate Institute’s Economic Impact Model for Electricity Supply (EIM-ES), we have estimated the potential impact on domestic employment over time resulting from the phase-down of fossil-based electricity and build-up of renewable electricity needed to achieve the JETP targets.

Authors analysis of employment in Indonesia in electricity supply sector jobs for a JETP-aligned scenario, including constructing new capacity as well as operation, maintenance and fuel supply, estimated using the EIM-ES.

Despite the large number of workers who will face lay-offs or voluntarily exit the coal industry, the expansion of renewable electricity, in particular solar PV, will stimulate overall considerably more new jobs over the transition period until 2050. As much as 500 GW of new renewable capacity needs to be added to the Indonesian grid in the coming three decades to align with the JETP targets of decarbonising the power sector by 2030, of which more than 300 GW is expected in the form of solar PV. By 2040, new jobs created by the expansion of solar PV will outweigh the number of jobs lost in coal value chains, including the construction and operation of plants, as well as domestic coal mining to supply the electricity sector. While the opportunity to shift to alternative renewable jobs is highlighted as a key benefit for coal workers in Indonesia’s just energy transition, the JETP process has given little attention to assessing how feasible this might be in reality.

The ongoing JETP process needs to set out policies and financial resources to address key barriers to the re-employment of coal workers

To put justice at the centre of the JETP, delivery plans should facilitate the re-employment of workers, as well as other forms of appropriate compensation, to support the communities that directly and indirectly depend on coal sector activities for income.

In our analysis we’ve estimated labour demand over time in the Indonesian coal sector, broken down into different parts of the value chain (plant construction, operations, and coal mining). Over the coming decades, as coal use is phased-down in Indonesia, some of these workers will exit the sector naturally through retirement as well as regular turnover. However, even after accounting for these using data on the age profile of the current workforce, around 180,000 workers involved in planning and constructing new coal plants may still be forced to find alternative employment by 2030. The following two decades may see further job losses for around 150,000 workers who are both operating and maintaining coal plants, as well as upstream workers in the coal mining sector (focusing on the share of Indonesian coal mining that supplies domestic electricity production).

When we look qualitatively at new jobs created and their comparability to jobs lost, in terms of skill transferability, geographic accessibility, financial attractiveness and timing, through the lens of a potential transition from the coal to the solar industry, it is clear there are a number of barriers to overcome.

| Barrier 1: Skills Gap | Alternative jobs in renewable employment industries will require coal workers to seek further education and training. We analysed how easily former coal workers might be able to find re-employment in the solar industry, by comparing their respective required qualifications (using data from the O*NET database). There are several high-skill jobs that are common to both coal and solar, including, for example, different types of engineers. These workers would likely be able to transition to similar jobs relatively quickly with minimal on-the-job re-training. However, many coal jobs have few transferable qualifications to solar jobs, which is mostly applicable to lower-skilled jobs in the mining industry. These workers may require up to two years of additional training. |

|---|---|

|

Recommendation: Mobilising public investment in the expansion of educational facilities, curriculum and staff as soon as possible, in anticipation of the large number of coal workers that will already exit the sector by the end of the decade. To ease some of the financial burden for individuals of investing in further education, JETP funds can be earmarked for coal workers in the form of re-training allowances to cover their costs. |

|

|

Barrier 2: Location |

Coal workers are currently not located where solar potential is highest. Indonesia’s coal production is concentrated in the regions of East Kalimantan, South Kalimantan and South Sumatra, which together make up almost 90% the country’s total coal output. The technical potential for solar PV, and hence where many of the jobs are likely to be based, is highest in Bali, Nusa Tenggara and parts of Java. The geographical shift in employment needs may require former coal workers and their families to permanently relocate to other regions within Indonesia to access new jobs. Relocation can cause additional financial burdens of re-homing and adjusting to a different cost of living, as well as personal challenges associated with loss of community, culture and place-based identity. |

|

Recommendation: JETP funds should be targeted at covering relocation costs for coal workers and families, particularly in Kalimantan and Sumatra, to help ease the burden for those moving in the short-term. These funds can also enable coal workers to find new jobs faster without having to build up enough financial means to be able to afford such a transition. |

|

|

Barrier 3: Salary |

Few other industries offer a comparable wage for coal workers, risking a reduction in living standards when looking for alternative jobs. Coal mining workers in Indonesia tend to be well-paid relative to their low level of education, receiving an average annual salary of USD 3,680. A wage premium in the mining sector is common across other countries too and is typically driven by strong labour union representation in the mining sector and/or premiums to compensate for the occupational health and safety risks associated with mining work. If workers seek jobs outside of mining or electricity supply, there are few other sectors that have a similar average level of education (high school or lower), except for manufacturing, water supply, construction, and hospitality but these have much lower annual salaries (USD 1,180 – 2,530). This means workers exiting the coal industry face the potential of a drop in their incomes and perhaps living standards when looking for alternative jobs. And this will affect not only the coal workers themselves, but also their financially dependent families and broader communities. |

|

Recommendation: To limit workers from taking low-paying jobs out of financial need after leaving the coal industry, JETP funds could offer a source of temporary income allowances for a defined period (coupled with re-training assistance) as financial support during their job search. |

Investments into measures to support coal workers’ transition must start now to ensure they are in place and accessible when needed

While Indonesia’s energy transition will boost jobs and drive industrial growth over the next decades, our analysis shows that there is more to ensuring a just energy transition than creating new employment. In order for coal workers to be able to take advantage of these new job opportunities, the energy transition must be accompanied by additional financial and institutional capacity-building, with funding clearly identified through the JETP’s investment plan.

Measures to support coal workers during their transition can include educational programmes, financial support for re-training and relocation and temporary income allowances. Some older coal workers, who might be less suitable for re-training or reluctant to relocate, could also be supported through early retirement provisions that enable them to maintain living standards.

To allow enough time to plan and implement these measures, investments need to start now, given the dramatic cut to the coal workforce expected already by the 2030’s. The goal of an energy transition which “leaves no-one behind” deserves more than just lip service if the CIPP is to live up to its “comprehensive” billing.

Authors: Lotta Hambrecht, Reena Skribbe, Harry Fearnehough

This blog is based on a Master’s thesis by Lotta Hambrecht, submitted to the Vienna University of Economics and Business, which she carried out in collaboration with NewClimate Institute, as well as a forthcoming joint research report by the NewClimate team and IESR.

|

The Economic Impact Model for Electricity Supply (EIM-ES) tool The EIM-ES is a transparent, Excel-based tool that estimates the domestic employment impacts of investments in the electricity supply sector within a country to aid policy decision makers. The model covers all relevant electricity generation technologies - both low carbon and fossil fuel-based plants – in order to provide an assessment of employment creation under different future pathways for the development of the electricity sector. It also provides information on wider economic indicators such as investment requirements, economic value added and trade. The tool has been used both by NewClimate Institute as well as other organisations and individuals to compare the magnitude of employment and other economic impacts under a range of scenarios in several countries, including: Argentina, South Africa, Indonesia, Thailand, Kenya, Australia, Mexico and Rwanda, with analysis ongoing in a number of additional countries. For more information, see our dedicated tool page: EIM-ES. |