Germany has increasingly focused on green hydrogen, and rightly so, as it is vital to decarbonising hard-to-abate sectors like heavy industry and meeting its climate targets. However, Germany cannot produce enough green hydrogen domestically to satisfy its energy demand. To address this shortfall, the government has adopted a new import strategy for hydrogen and its derivatives last month, aiming to secure a stable, reliable, and diversified supply. While the strategy is designed to ensure energy security and support the country’s emerging hydrogen market, it will also have significant implications for countries investing in hydrogen production for export, especially those in the Global South.

The import strategy outlines a framework to meet Germany’s predicted demand for hydrogen and its derivatives, which the government estimates will reach 95 to 130 terawatt hours (TWh) by 2030. About 50 to 70 percent of this demand will need to be covered by imports, according to estimates by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK), making Germany one of the world’s largest hydrogen importers in the future. The strategy identifies hydrogen derivatives, such as ammonia and methanol, as essential components of the import plan. It also includes plans to expand Germany’s import pipelines and shipping infrastructure and to closely cooperate with partner countries on hydrogen.

Unveiling the import strategy, German Economy Minister Robert Habeck said: “It sends a clear signal to our partners abroad: Germany expects a large and stable domestic demand for hydrogen and derivatives and is a reliable partner and target market for hydrogen products.” Further, he hailed it as creating “investment security for partner countries.”

But is the signal clear and reliable for exporting countries? What caveats should they be aware of? In this article, we unpack Germany’s hydrogen import strategy and highlight three key considerations for Global South countries looking to export hydrogen to Germany.

Stiff competition for distant Global South countries in hydrogen exports to Germany

The German government estimates that the total demand for hydrogen will reach 95-130 TWh in 2030 but does not specify a breakdown between ‘molecular’ hydrogen (referring to gaseous and liquid forms of hydrogen) and its derivatives. By 2045, the total demand is projected to reach 360 to 500 TWh for molecular hydrogen and around 200 TWh for derivatives. This corresponds to a projected increase in total hydrogen demand of 9 to 11 times the current level (55 TWh), indicating substantial growth expectations.

Germany expects 50 to 70 percent of this projected hydrogen demand to be met with imports from sources both within and outside Europe, via pipeline or ship. This translates to a total import demand of up to 95 TWh by 2030, including both molecular hydrogen and derivatives. By 2045, import demand reaches up to 250 TWh for molecular hydrogen and 140 TWh for derivatives.

The strategy states that molecular hydrogen can be transported most cost-effectively via pipelines, which will connect Germany with suppliers in Europe as well as nearby regions, such as the North Sea, Baltic Sea, and Mediterranean Sea. In the short term, however, Germany is open to importing hydrogen derivatives via ship and converting it back to molecular hydrogen, in case domestic and regional production is insufficient to fulfil immediate demand. The strategy expects that lower production costs in renewable-rich exporting countries in the Global South can partially offset high conversion losses and transport costs – an assumption that may not hold up in reality.

As European hydrogen production capacity and pipeline infrastructure expand over time, Germany may find it more economical to increase imports from geographically closer neighbours, thereby saving on transport costs and reducing energy losses. Distant Global South countries would then be best placed to supply hydrogen derivatives, which are more suitable for ship-based transport, but for which the import demand is unspecified in the short term and relatively smaller in the long term (140 TWh by 2045).

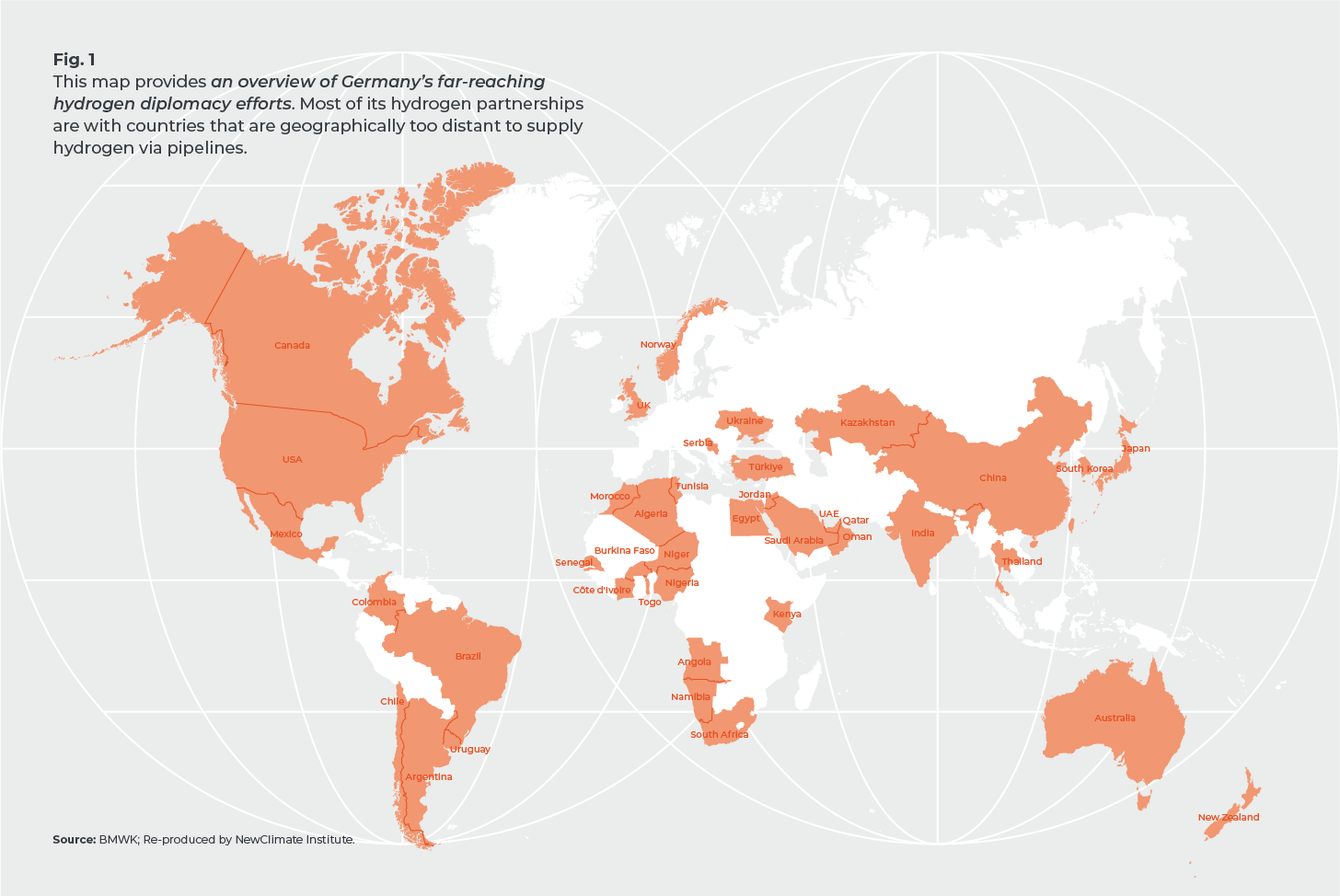

For Global South hydrogen producers looking to export mainly via ship, competition for hydrogen exports to Germany is likely to be intense. Germany has hydrogen cooperation partnerships with 38 non-European Union countries, ranging from explicit bilateral agreements to other forms of hydrogen support activities. Even if the projected demand for ship-based imports fully materialises, it will still represent relatively small individual shares for Global South partners. Therefore, it would be important for these countries to diversify their export strategies, explore regional markets to supply more cost-competitively, and develop domestic offtake opportunities that can also support local decarbonisation efforts.

Economic risks of investing in low-carbon hydrogen production

Germany’s primary goal with its import strategy is to ensure a reliable supply of green, sustainably produced hydrogen in the long term. To meet immediate demand and facilitate the scaling up of hydrogen use, the government indicated it would also purchase low-carbon hydrogen and its derivatives.

Germany’s decision to import low-carbon hydrogen, however, has faced criticism for potentially delaying the transition to zero-carbon sources like green hydrogen and hindering the expansion of renewable infrastructure. Green hydrogen, produced using renewable energy sources such as wind and solar, generates zero carbon emissions and is the only type of hydrogen that can truly contribute to reducing global emissions. In contrast, low-carbon hydrogen, often referring to blue hydrogen, is produced from gas using carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) technology. CCUS captures and stores most, but not all, of the carbon dioxide emissions from the production process, making it less polluting but not a zero-carbon solution.

The German government, however, has signalled a long-term preference for green hydrogen. In its import strategy, it explicitly ruled out financial support for low-carbon hydrogen production projects. While the strategy does not specify the exact types or proportions of low-carbon hydrogen it plans to import, it suggests that low-carbon hydrogen is intended to address short-term demand.

Focusing on low-carbon hydrogen production may provide short-term market opportunities for some countries but poses significant economic risks. CCUS requires substantial upfront investments, which might not be recouped as green hydrogen becomes more cost-competitive and demand for low-carbon hydrogen in Germany and Europe diminishes. Countries investing in low-carbon hydrogen projects now, particularly those in the Global South, risk facing stranded assets and being locked into their fossil fuel infrastructure, such as gas plants and pipelines. Therefore, it would be more prudent for these countries to invest in infrastructure that supports green hydrogen production, which offers long-term demand certainty and aligns with their own decarbonisation efforts.

Lack of detail on social and environmental safeguards and local value creation opportunities

As part of its hydrogen import strategy, the German government is committed to ensuring a socially just and sustainable energy transition for both Germany and hydrogen-exporting partners, particularly those in the Global South. The strategy emphasises Germany’s intention to co-develop high standards in partnership with exporting countries to mitigate social and environmental risks of hydrogen projects while contributing to improved local living conditions. This includes ensuring sustainable resource use, respecting Indigenous peoples' rights, enhancing access to energy and clean drinking water, promoting occupational safety, encouraging local participation, and fostering local value creation. At the same time, the strategy stresses the need for these standards to be pragmatic to ensure a stable and sufficient hydrogen supply to Germany.

This raises important questions: What will Germany do if its energy security interests conflict with its goal of social and environmental protection for producer countries? The strategy envisions a central role for German companies in these international activities, which may involve establishing local operations to strengthen their market position and promote German technology exports. How will Germany ensure local value creation and technical capacity building if these goals clash with German business and trade interests? Despite its stated commitment to share the risks and benefits of hydrogen development, the strategy lacks specifics on how these standards will be developed and enforced to safeguard local interests.

Green hydrogen presents significant development opportunities for renewable-rich countries in the Global South, including industrial growth, job creation, infrastructure development, improved trade balance, and increased access to energy and water. These countries should ensure that their sustainable development priorities are clearly reflected in their hydrogen cooperation agreements with Germany. International partners such as Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) can help by providing legal support for Global South producer countries in negotiating these agreements. Germany, too, should ensure that its commitment towards mutually beneficial partnerships translates into reality and leads to socially just, development-centred energy transitions in the Global South.

Written by Hyunju (Laeticia) Ock, Writer and Editor & Chetna Hareesh Kumar, Climate Policy Analyst at NewClimate Institute