Asset managers, asset owners and other financial institutions manage much of the capital required to transition to low-carbon economies globally, but can we rely on them as financiers of change? Evidence from Reclaim Finance, Urgewald, and Greenpeace shows that even financial institutions committed to net-zero initiatives under the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ) continue to invest billions of dollars in fossil fuels through both stocks and bonds, not to mention providing other services like underwriting and insurance.

Why do financial institutions continue to back fossil fuel expansion, which is clearly not in line with the Paris Agreement nor with many financial institutions’ own net-zero targets?

This blog reveals three critical limitations in the voluntary approach of financial institutions’ net-zero targets: the low integrity of existing targets, their limited ability to directly control investee emissions, and a finance-first mandate that hinders voluntary climate action. We call for a reassessment of strategies that can effectively drive investments towards real-world decarbonisation.

#1 Financial institutions’ net-zero targets lack credibility

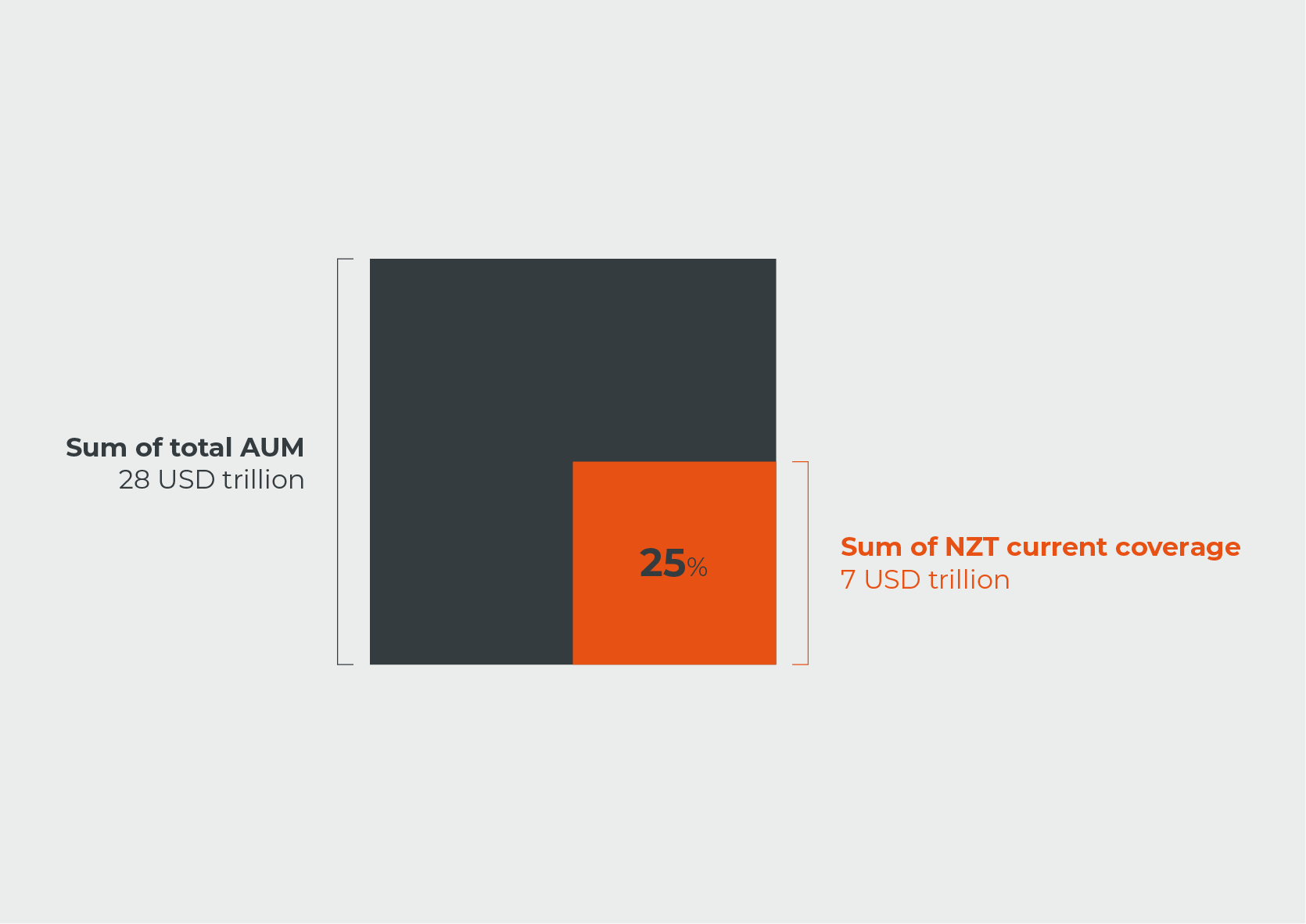

Despite the buzz around net-zero in the sector, targets set by financial institutions often do not adhere to rigorous net-zero requirements, which include comprehensive coverage of all Assets Under Management (AUM). NewClimate found that only 25% of the total AUM of the largest 50 asset managers are currently covered by net-zero targets (see Figure 1). This leaves the majority of assets unaddressed by targets, potentially posing a significant risk for hidden emissive assets. As demonstrated in a report by Danu Insights, even if net-zero targets cover 90% of AUM, this can still exclude up to 85% of emissions, as all the high-emission assets may be concentrated in the remaining 10%.

Adding to the problem, very few financial institutions are reporting or setting targets for their investees' scope 3 emissions. As a result, if a financial institution holds oil and gas companies in its portfolio, it essentially ignores any responsibility for the emissions associated with the combustion of the fossil fuels produced by these companies. Data scarcity for some sectors understandably limits financial institutions’ ability to set more comprehensive targets. However, to ensure that net-zero targets serve as a meaningful metric for gauging decarbonisation progress, they would need to encompass a financial institution's entire investment portfolio and include investees' scope 3 emissions.

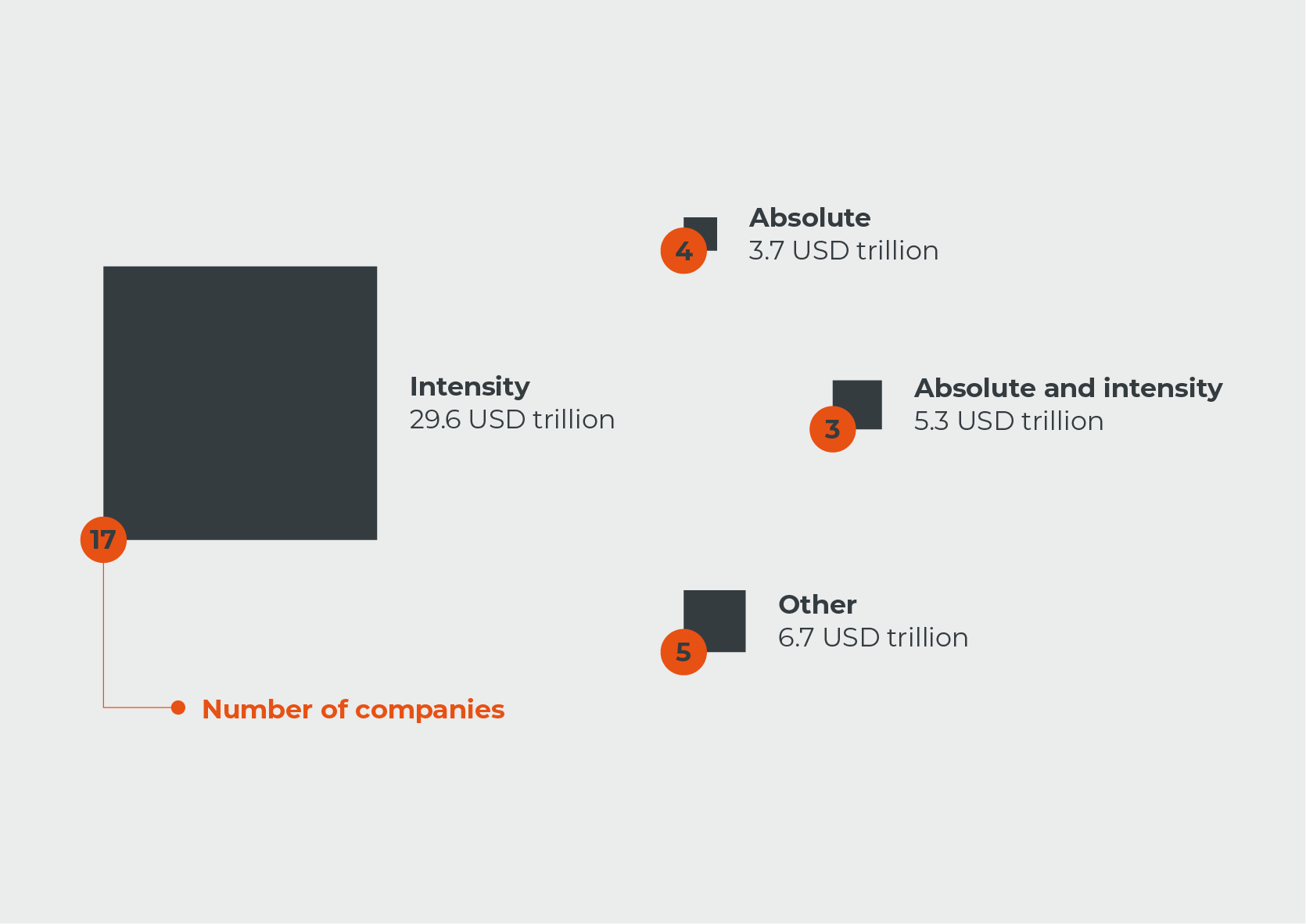

Furthermore, many financial institutions persist in setting economic or physical intensity-based targets, which fail to provide a meaningful indication of decarbonisation progress (see Figure 2). Proponents of this approach claim that by reporting on progress as emissions per dollar invested or output of a product, one can measure value gains associated with emissions. However, intensity measures can also conceal an increase in absolute emissions.

To accurately assess if financial institutions are aligned with the Paris Agreement, it is essential to implement sector-specific absolute restrictions on specific investment types such as new coal, oil, gas, and related value streams, as recommended by the UN’s High-Level Expert Group. Intensity-based targets can provide additional information, but do not suffice on their own. Without adhering to credible and comprehensive target-setting, questionable net-zero targets will continue to mislead about financial institutions’ true ambition. This issue is gaining more recognition among industry stakeholders. For example, the UNEP FI’s recent Net Zero Asset Owner Alliance (NZAOA) target setting protocol encourages financial institutions to move beyond emissions accounting to more decarbonisation-specific goal setting.

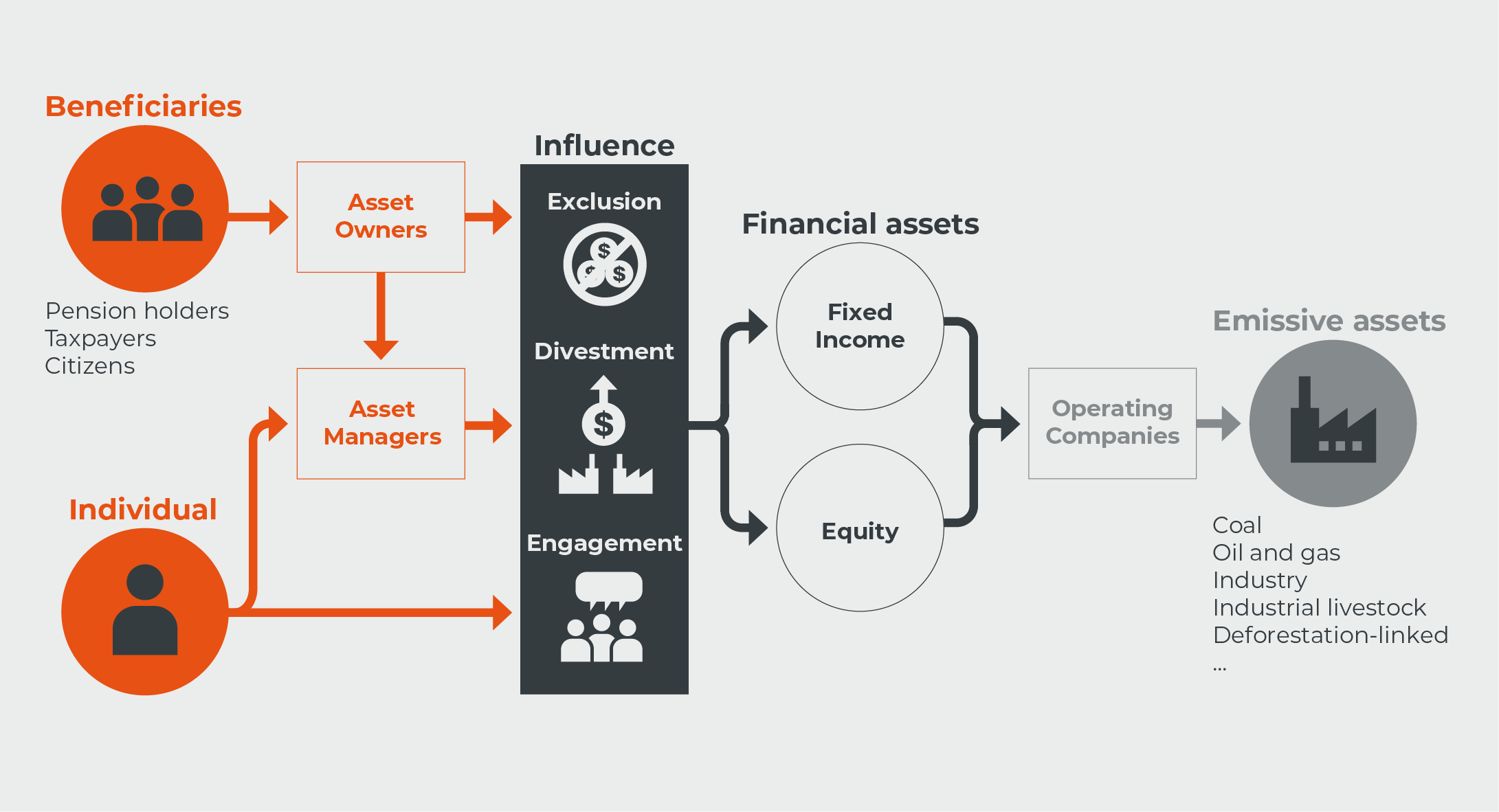

#2 Financial institutions do not have direct control over real economy emissions

Although financial institutions hold responsibility for their financed emissions, they do not have direct managerial control over their investees' GHG emissions in the real economy (see Figure 3). It is commonly believed that withholding funding (excluding) or divesting from a company is a powerful lever to force companies to decarbonise. However, in efficient markets such as public equity, individual financial institutions are unlikely to effectively constrain capital for emissions-intensive assets as other financial actors can just take over these divested assets. Highly emitting assets simply move from one balance sheet to the next, with the new owner potentially showing less concern about their impact on the climate. The potential for influence is stronger in primary and specifically in fixed income markets. However, even in these markets, financial institutions have no direct control over emissive assets.

Financial institutions, however, are not without agency. In fact, it falls within their fiduciary duty and corporate stewardship responsibilities to actively engage with investee companies. This includes ensuring that investments align with strategic objectives and risk tolerance to safeguard shareholder value, a mandate that extends to addressing climate risks. Nevertheless, engagement strategies concerning climate risks remain largely underutilised, even among financial institutions committed to ambitious targets.

#3 Financial institutions’ short-term profit mandate overshadows ambitious voluntary climate action

Why do financial institutions overlook the compelling reasons to take more ambitious climate action? Despite the mandate for financial institutions to manage climate risks, conventional markets suffer from a ‘tragedy of horizons’. This means that the true risks of the climate crisis are frequently omitted from financial decision-making processes as they seem costly and far in the future. Instead, short-term private profits take precedence over factoring in the longer-term collective risk and damage related to climate change.

Existing regulatory measures aimed at addressing this issue have largely focussed on providing the disclosure of physical and transition risks, for example through the Taskforce for Climate-related Financial Disclosure. However, information disclosure alone has not made these risks material to financial institutions yet. The underlying problem is not just information asymmetry, but also underpriced climate-related risks and externalities causing a far-reaching market failure.

Attempts to regulate the real economy in response to this market failure are facing opposition from powerful asset owners with profit aligned-interests who vehemently lobby against such policies. Voluntary initiatives like the NZAOA have served their purpose in mobilising financial institutions to think about methods and strategies to align finance with climate change mitigation. Now, it is time to turn rhetoric into reality and effectively address this market failure. Binding regulation is needed to set Paris-aligned incentive structures for the financial sector. Otherwise, financial institutions have no voluntary incentives to change investment behaviours in the short to medium term, and consequently, their voluntary net-zero targets make little sense.

Time to come to our senses

In light of these flaws, there is a clear need to reassess what approaches effectively shift investment towards driving tangible change in the real economy. As the financial sector holds a crucial role in supporting the transition of economies, regulators should establish an environment that advances the entire sector towards a low-carbon economy. Without such pressure in place, considerable time and effort are wasted on overengineered target-setting methodologies and largely symbolic commitments, all while carbon-intensive investments continue to thrive as a profitable business model.

Recognising the urgency of this task, NewClimate is looking to explore alternatives as part of the EU Horizon grant project Achieving High-Integrity Voluntary Climate Action (ACHIEVE). We encourage stakeholders to reach out to us and collaborate on catalysing transformative change for the world of finance.