Under the Copenhagen Accord, developed country governments agreed to mobilize 100 billion USD of climate finance each year as of 2020. This target focuses on increasing financial flows to mitigation and adaptation activities in developing countries. The Paris Agreement sets a new challenge for domestic and international finance flows: Article 2.1 names “making finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development” as one part of the global response to the threat of climate change. This compares to the target to mobilize climate finance in various ways:

- The Paris Agreement means that every investment needs to be climate resilient and consistent with the Agreement’s long-term mitigation goal of limiting global warming to well below 2°C and pursuing 1.5°C. This goes beyond the Copenhagen Accord, that did not refer to finance flows beyond climate finance and rather focused on mobilizing additional finance for mitigation and adaptation. When looking at aligning finance with the Paris Agreement, we speak about shifting investments that undermine the Paris Agreement to areas that actively support it or do not interfere with reaching its objectives.

- The Paris Agreement requires a redefinition of mitigation finance from “emission reductions” to “aligning with the Paris Agreement mitigation goal”. Emissions reductions are required, but every reduction has to be compatible with Paris-aligned pathways. For example, investments in efficiency improvements of fossil power plants reduce emissions in the short term but may induce a long-term lock-in in carbon intensive technologies or risk stranded assets.

MDBs regularly report on the climate finance they have helped mobilize, and in this context have developed eligibility criteria both for mitigation and adaptation, and created a list of typologies to be counted as climate mitigation finance. The joint climate finance group of MDBs and the International Development Finance Club (IDFC) have adjusted the method over the course of time and increased its stringency, and more recently directly refer to compatibility with low-emissions pathways as mentioned in the Paris Agreement. As COP24 started, the MDBs announced a joint framework for working towards Paris alignment and will share insights on their work towards a common set of principles for post-2020 reporting.

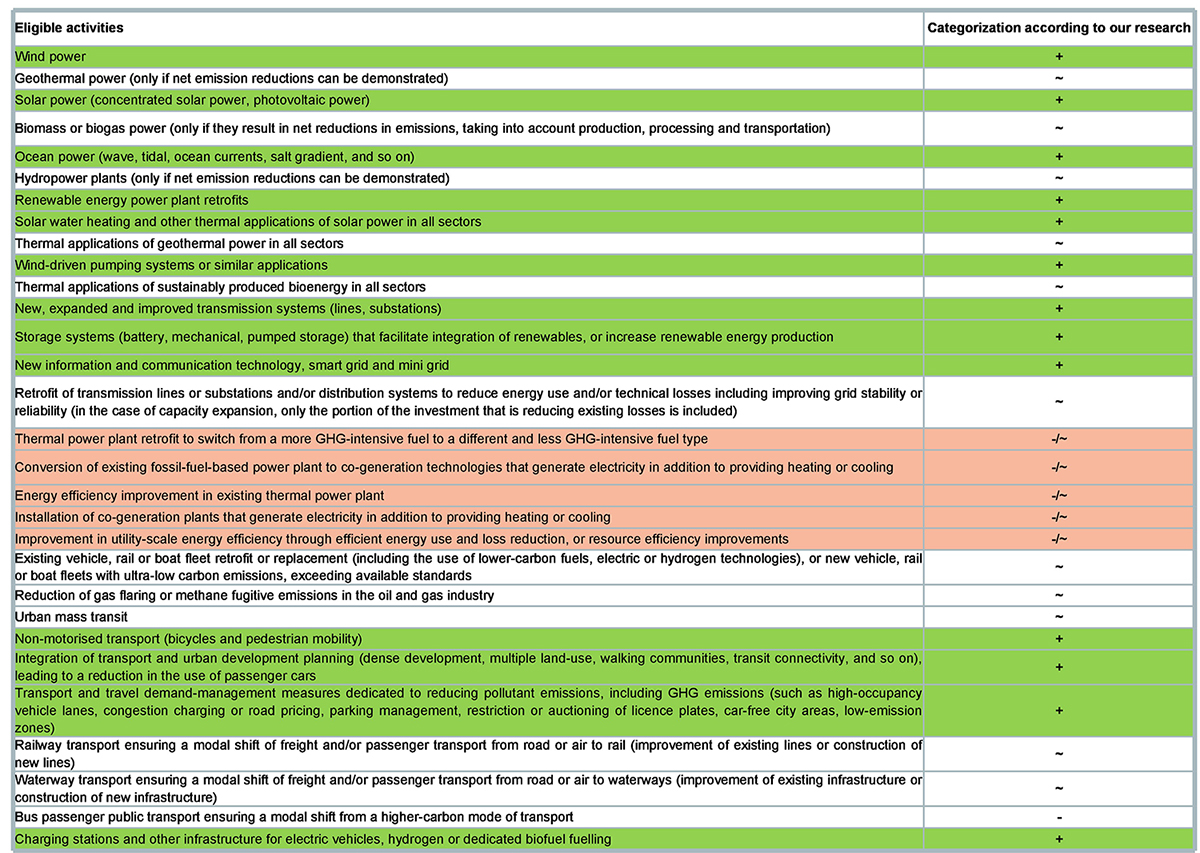

In our working paper on Paris alignment[1], we categorize investment areas in “Paris-aligned”, “misaligned” and “conditional”. Paris-aligned means investments actively support the mitigation goals of the Paris Agreement and will remain part of the system in the long term. Misaligned means they undermine those goals and need to be phased-out quickly. For investment areas and technologies under “conditional” it depends on the exact circumstances and characteristics of a project whether it can be considered Paris-aligned.

The conditional category includes investment areas that generate some level of greenhouse gas emissions, or that carry significant risk for other sustainability criteria. It also includes investment areas that are essential for the Paris Agreement and actively support its implementation, such as efficiency improvements or electricity grids. The question here is how ambitious the project should be and how to ensure it does not negatively interfere with aligned investment areas, not whether there should be an investment at all. The conditions the investment would need to meet to be considered aligned are:

- Alignment with cost-efficient transformation to net-zero emissions in the second half of the century.

- Ensuring that the century mid-point is approximately the cut-off date for energy-related emissions.

- No negative interference with aligned investment areas or sustainable development.

This briefing compares the MDB’s eligibility criteria to our categorization of different investment areas in “aligned”, “misaligned” and “conditional”, for the sectors we covered in depth (energy supply and transport infrastructure). The MDB’s text on eligibility accompanying the typology list also picks up some of the conditionalities we have identified. For example, it states that projects that are included in the typology but nevertheless emit significant amounts of GHG because of specific circumstances (e.g. a hydro power plant with high methane emissions from flooding land) should be identified. The MDB description of eligibility stresses that the typology excludes projects that reduce emissions but lock in carbon intensive technologies.

Table 1 illustrates a comparison of the MDBs’ list of eligible activities to the categorization in our research, for the focus areas energy and transport infrastructure. More detail is available in this detailed table for download.

Categorization of eligibility criteria for climate finance of the MDBs. Green (+) is aligned, red (-) is misaligned, white (~) is conditionally aligned.

We find that about half of the MDB’s typologies in sectors we covered would fall in the aligned category, and thus actively support the Paris Agreement mitigation goal. Of the remaining items, about 2/3 are conditionally aligned, meaning further considerations would be needed to determine whether the investment is aligned with the Paris Agreement. There are also various items in the list, where a categorization is not possible, given that the fuel type of the installation is not specified. If the investment was to target improvements of coal or oil-based installations, it would be misaligned. For gas-based installations, additional considerations would be necessary, and for low-carbon options the investment would be aligned.

To further improve the eligibility criteria for climate finance and work towards aligning investments with the Paris Agreement, the MDBs could break down the criteria for eligibility further (e.g. differentiate by fuel) and define increasingly strict benchmarks (e.g. a minimum efficiency level) in line with net-zero CO2 emissions around 2050. This would move the eligibility criteria into a direction where the complete MDB mitigation related climate finance would actively support the Paris Agreement temperature goal. Additionally, a requirement to report all other investments would make transparent that they do not contradict the Paris Agreement.

[1] Germanwatch and NewClimate (2018), Aligning with the Paris Agreement Temperature Goal – Challenges and Opportunities for Multilateral Development Banks.

Contacts:

Hanna Fekete, Frauke Röser, Leonardo Nascimento and Aki Kachi, with contributions from Sophie Bartosch and Lutz Weischer (Germanwatch)