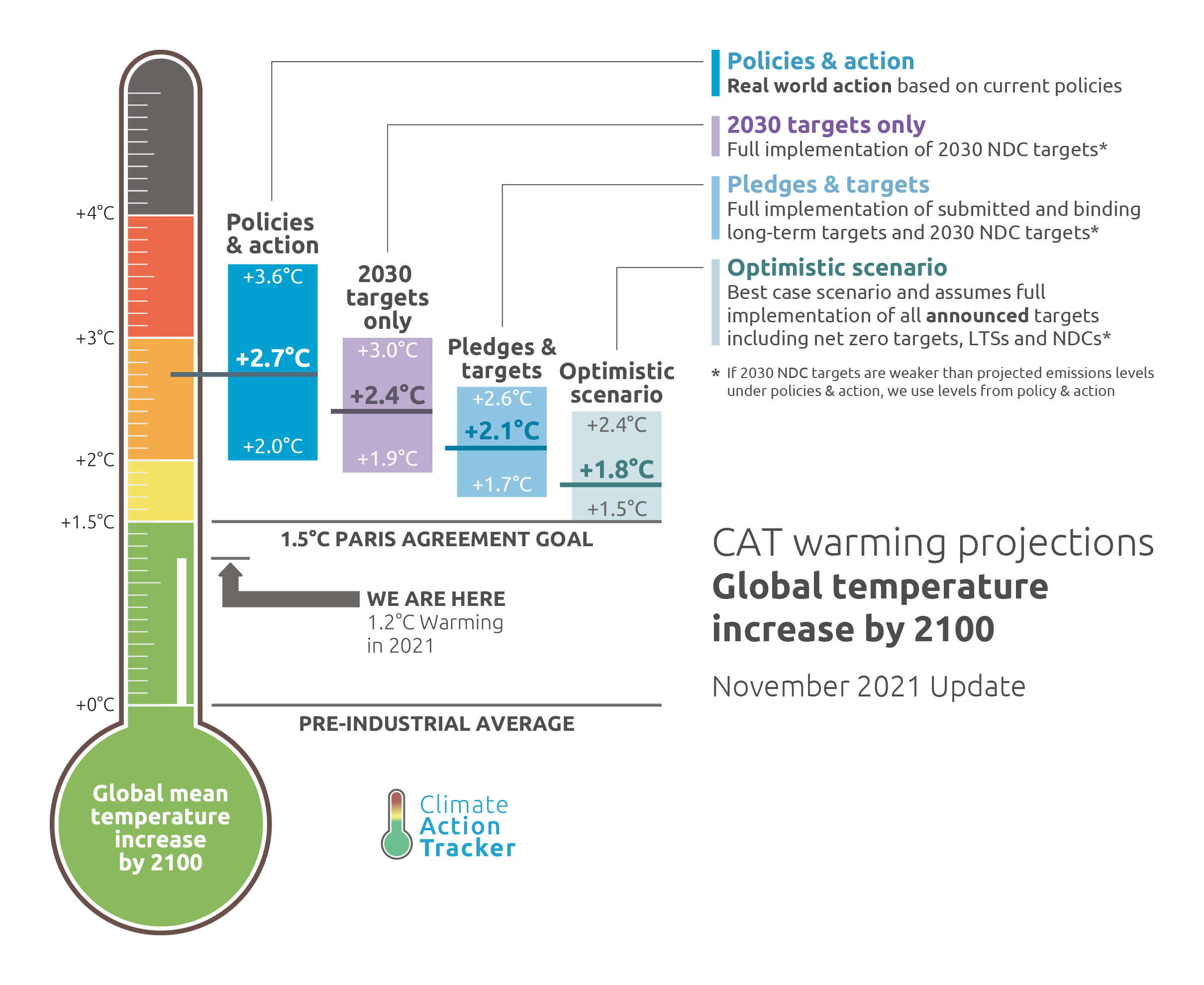

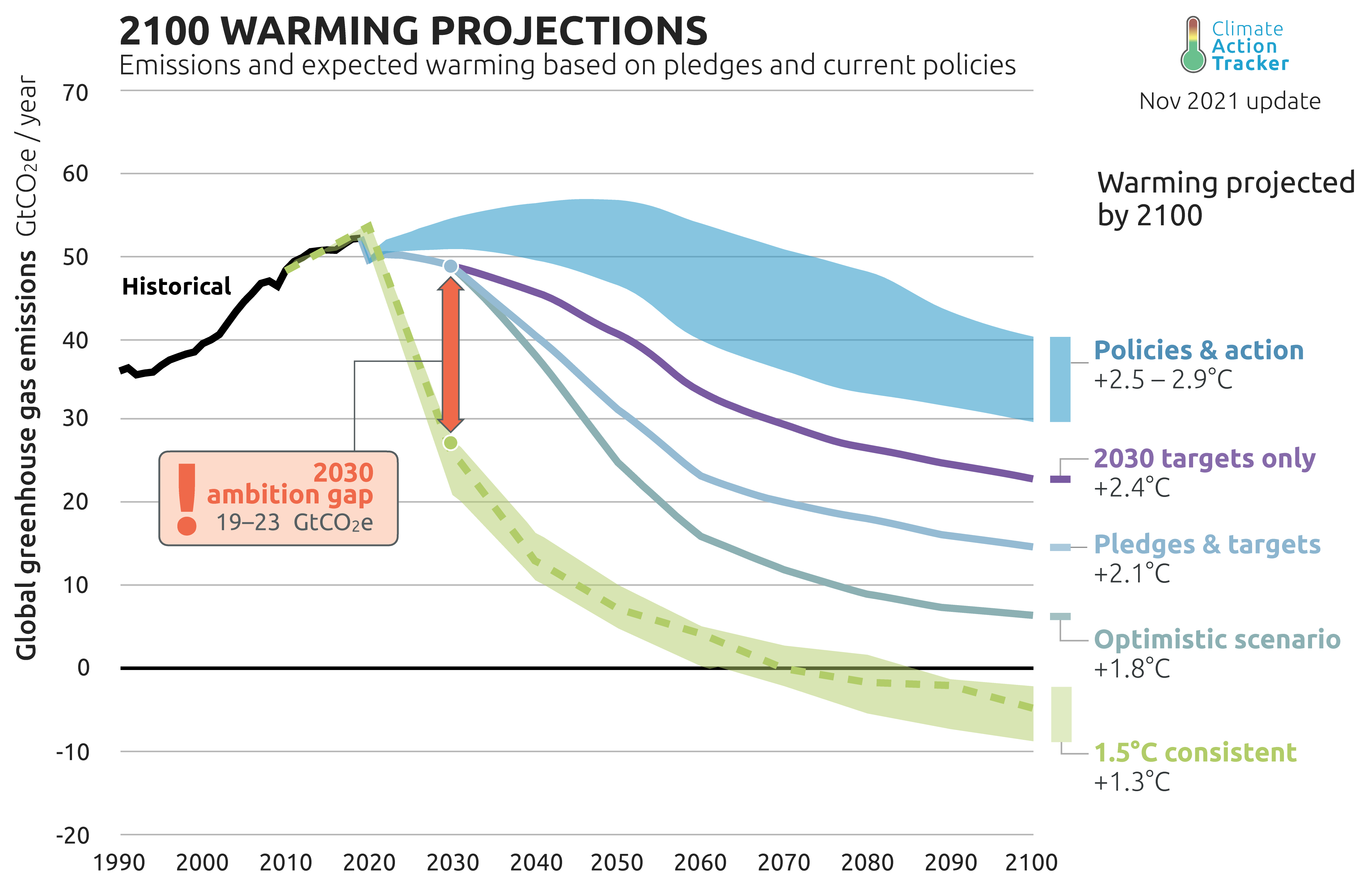

Glasgow has a credibility gap between talk and action. In this briefing, the Climate Action Tracker (CAT) has calculated that if all governments met their 2030 targets, we would have 2.4˚C of warming in 2100. But right now, current policies put us at 2.7˚C.

Summary

In Paris, all governments solemnly promised to come to COP26 with more ambitious 2030 commitments to close the massive 2030 emissions gap that was already evident in 2015. Three years later the IPCC Special Report on 1.5°C reinforced the scientific imperative, and earlier this year it called a climate “code red.” Now, at the midpoint of Glasgow, it is clear there is a massive credibility, action and commitment gap that casts a long and dark shadow of doubt over the net zero goals put forward by more than 140 countries, covering 90% of global emissions.

Impacts on temperature estimates

Policy implementation on the ground is advancing at a snail’s pace. Under current policies, we estimate end-of-century warming to be 2.7°C. While this temperature estimate has fallen since our September 2020 assessment, major new policy developments are not the driving factor. We need to see a profound effort in all sectors, in this decade, to decarbonise the world to be in line with 1.5°C.

Targets for 2030 remain totally inadequate: the current 2030 targets (without long-term pledges) put us on track for a 2.4°C temperature increase by the end of the century.

Since the April 2021 Biden Leaders’ Summit, our standard “pledges and targets” scenario temperature estimate of all NDCs and submitted or binding long-term targets has dropped by 0.3°C to 2.1°C, but this improvement is due primarily to the inclusion of the US and China’s net zero targets, now that both countries have submitted their long-term strategies to the UNFCCC.

Insufficient momentum

There has been insufficient momentum from leaders and governments to increase 2030 climate targets ahead of, and at, Glasgow: NDC improvements submitted over the last year have reduced the emissions gap in 2030 by only 15-17%. The biggest absolute contributions to this narrowing come from China, EU and the US, though other countries with lower emissions levels have also improved their NDCs.

Contrary to the Paris Agreement’s requirement that each NDC update is a progression beyond the last, several governments have only resubmitted the same target as 2015 (Australia, Indonesia, Russia, Singapore, Switzerland, Thailand, Viet Nam), or submitted an even less ambitious target (Brazil, Mexico). Some have not made new submissions at all (Turkey and Kazakhstan), and Iran has yet to ratify the Paris Agreement. Even with all new Glasgow pledges for 2030, we will emit roughly twice as much in 2030 as required for 1.5°. Therefore, all governments need to reconsider their targets.

Targets must be fully implemented

Globally, around 90% of emissions are now covered by net zero targets. While these targets are an important signal, and some have accelerated governments’ climate action, the quality of most remains questionable. If all the announced net zero commitments or targets under discussion are implemented, this would bring our temperature estimate for this “optimistic scenario” down to 1.8°C by 2100, with peak warming of 1.9°C. But this is only IF these targets are fully implemented, and it’s a big IF. Our analysis shows countries with an “acceptable” net zero rating cover only 6% of global emissions.

No single country that we analyse has sufficient short-term policies in place to put itself on track to its net zero target. The net zero CAT assessment also includes announcements made by governments which are not backed up by any national legislation, nor plans. Some lack critical information to allow for a full evaluation of the target’s likely impact, including whether net-zero is defined as CO2 only or covers all greenhouse gases. It also needs to be emphasised that our ‘optimistic’ assessment of end-of-century median warming of about 1.8°C is not Paris Agreement compatible and that warming of 2.4°C or more cannot be ruled out.

2030 actions and targets are more often than not inconsistent with net zero goals, so that the gap between current policies and net zero goals is now 0.9°C. This, we consider, is the credibility gap that Glasgow needs to address.

The key drivers for this appalling outlook are coal and gas

Coal: To meet the Paris Agreement’s 1.5˚C warming limit, coal must be phased out of the power sector by 2030 in the OECD, and globally by 2040. But in spite of political momentum and clear benefits beyond climate change mitigation, there is still a huge amount of coal in the pipeline, for example in China, India, Indonesia and Viet Nam, and too many countries, including Japan, South Korea, Australia, still have plans centered around coal as a major contributor to electricity generation in 2030. Some also continue funding coal projects abroad. While some of these governments have committed in Glasgow to phasing out coal, we need to see that reflected on the ground at home. All targets have yet to be supported by ambitious policies. Our temperature estimate of all adopted national policies (‘current policies’ scenario) is 2.9°C.

Natural Gas: The increasing use of natural gas is not Paris Agreement compatible, yet we are seeing the gas industry push and promote their product, supported by governments across the world. In the six years since the Paris Agreement, CO2 emissions from gas grew by 9%, whereas emissions from coal and oil are down. Gas for electricity generation, as with coal, needs to peak in this decade, and largely be phased out globally in the coming decades, and for other applications soon after, if the world is to reach net zero CO2 by 2050. In Southeast Asia, heavily coal-dependent countries are now considering a switch from coal to gas (e.g. Viet Nam), rather than directly to renewables, large infrastructure for natural gas is also under development in Europe (Nord Stream 2 for imports from Russia), Canada (expansions of pipelines for export), Australia and the USA (LNG exports), and multiple African countries are promoting the increased production and use of natural gas.

Methane and Forestry: Global methane and forestry initiatives announced in Glasgow support important actions, but these must go beyond existing national targets to be impactful: the Global Methane Pledge – of reducing methane emissions by 30% in 2030 – has the maximum potential to reduce the 2030 emissions gap by 14%, and warming by -0.12°C by 2100. But much of this potential is already included in existing climate pledges. The US is a prime example: the methane reduction target is already partially included in its long-term strategy, which we have already included the effect of in our ‘Pledges and Targets’ temperature estimate. Similarly, the Global Forestry Finance pledge can result in additional climate mitigation only if this finance is additional to the current promised funding and does not cut funding for other mitigation measures. Since the USD 100bn goal has not yet been met, the additionality of this new initiative is questionable, at best.

Glasgow must address the credibility gap

While the warming outlook has improved since Paris, the bottom line is that despite all the net zero promises, inadequate real-world action unable to deliver the kind of climate action that is aligned to the 1.5˚C temperature limit: in 2015, ahead of the Paris Agreement, the CAT estimated current policies would lead to warming of 3.6°C, and the submitted targets would lead to 2.7°C. Six years later, the warming from current policies has now come down to 2.7°C. If governments were to achieve their 2030 NDC targets and binding long-term targets (LTS), temperature increase could be limited to 2.1°C.

If governments are serious about the Paris Agreement’s temperature limit and their own net-zero goals, they need to translate those long-term goals into net-zero aligned ambitious 2030 targets and implement the necessary policies today. Developed countries will also significantly increase the climate finance available to support the transition. Until this happens, there is no cause for celebration.